The Costume Identity Lab

on Halloween, identity exploration, and what psychology tells us about the masks we wear

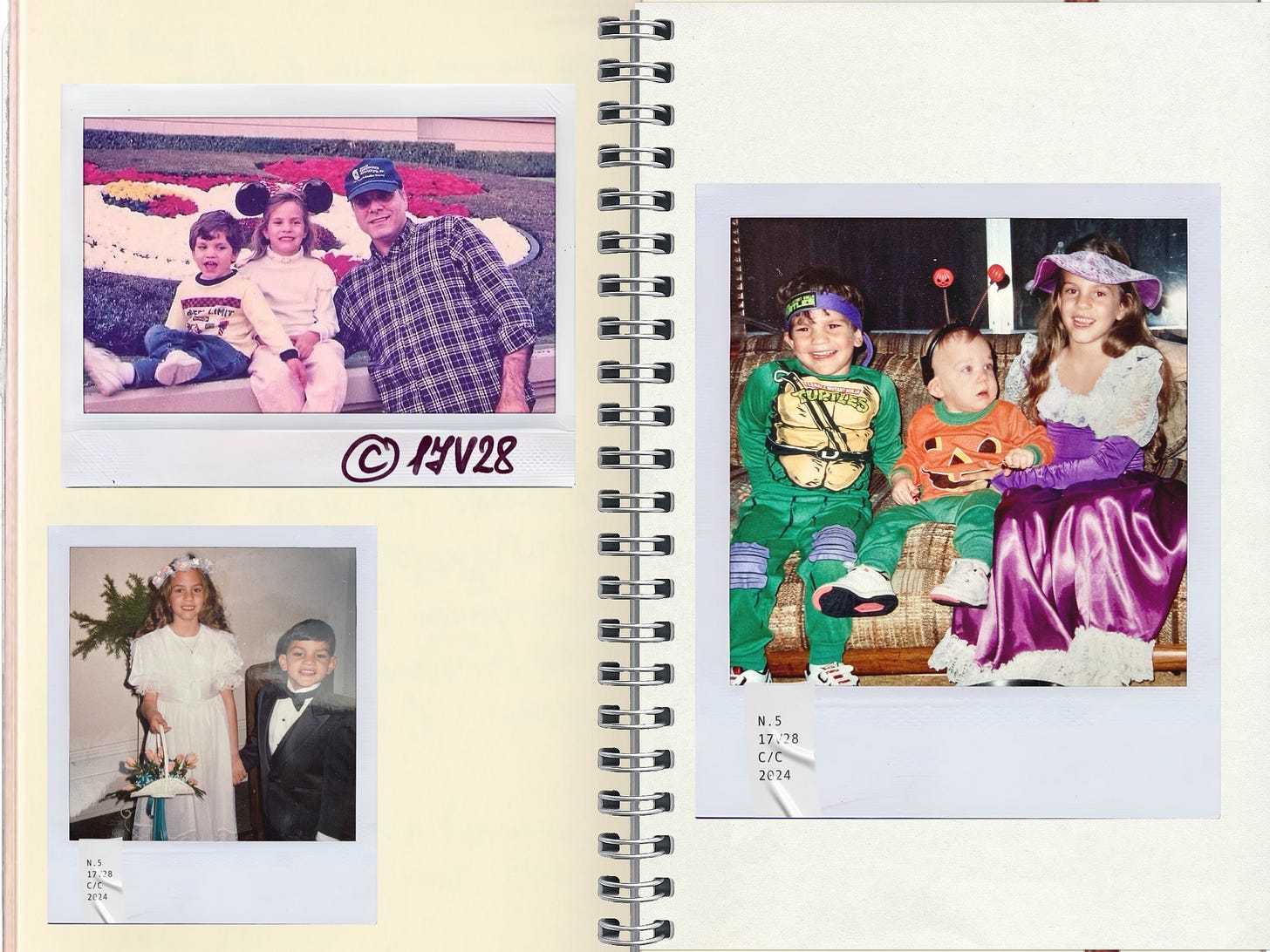

It’s golden hour in our household and the shadows playfully shift on the pale walls surrounding me. I’m squinting my eyes as I dig around in my two-year-old son Teddy’s closet. The hangers slide to and fro on the rod, a collared baby blue Polo shirt here and some OshKosh overalls there, all the way to the end of the line. That’s where I spot the garment I’ve been searching for, cloaked in the shadows. Yes, there it is!

Teddy’s Superman costume!

I grab it and cross the hallway into the master bedroom. Here, I find Ralphie, my four-year-old human exclamation mark of a son, energetically examining every piece of his Batman costume that I had laid out on the bed three minutes prior. He swings the black zig-zag cape in the air, whooooosh, whoooooosh, before putting it over his head and gurgling, “I’m a ghost, mommy!”

“Oh my!” I play along.

Ralphie pulls off the “ghost” cape and blurts out, “Ahhhh—I tricked you! It’s just me!”

I laugh as I take Teddy’s costume off its hanger and place it gently on the bed. Ralphie holds up the Batman mask to his face, giggling and bouncing around while he tries to maneuver the elastic cord over his head. As I help him situate the mask on his face, I notice that he is positively beaming—his sheer enthusiasm is palpable.

There’s actually a word to describe this moment, to describe the precise sense of freedom that wearing a mask confers: maskenfreiheit. There’s something psychologically liberating about putting on a mask, if only for a little while.

Next thing I know, Teddy comes barreling into the room, immediately grabbing his Superman costume off the bed. After getting dressed, the two brothers, or should I say the “bubbas,” seem pretty psyched about their heroic glow-ups.

I never want them to grow up, I think.

Watching them, I feel a pang about their fleeting childhood. And beneath that, another longing brews in the cauldron of my mind that beckons to rediscover something I’ve lost, or maybe never fully claimed.

That’s when it hits me: I miss that maskenfreiheit in my own life. That freedom to transform. That permission to try on identities just to see how they fit. That liberation of being someone new, if only for a few hours.

The older you get, the further away you travel from that. What was once a vibrant palette rich with so many shades of possibility and exploration has likely now been toned down, muted, and greyed by the constraints of habituation.

And I can’t help but wonder:

How has your identity crystallized by the time you reach early adulthood?

I miss all the opportunities to try on different identities that my youth afforded me. When did I stop believing I could explore being something or someone different than who I am today? What happened to that curious sense of exploration?

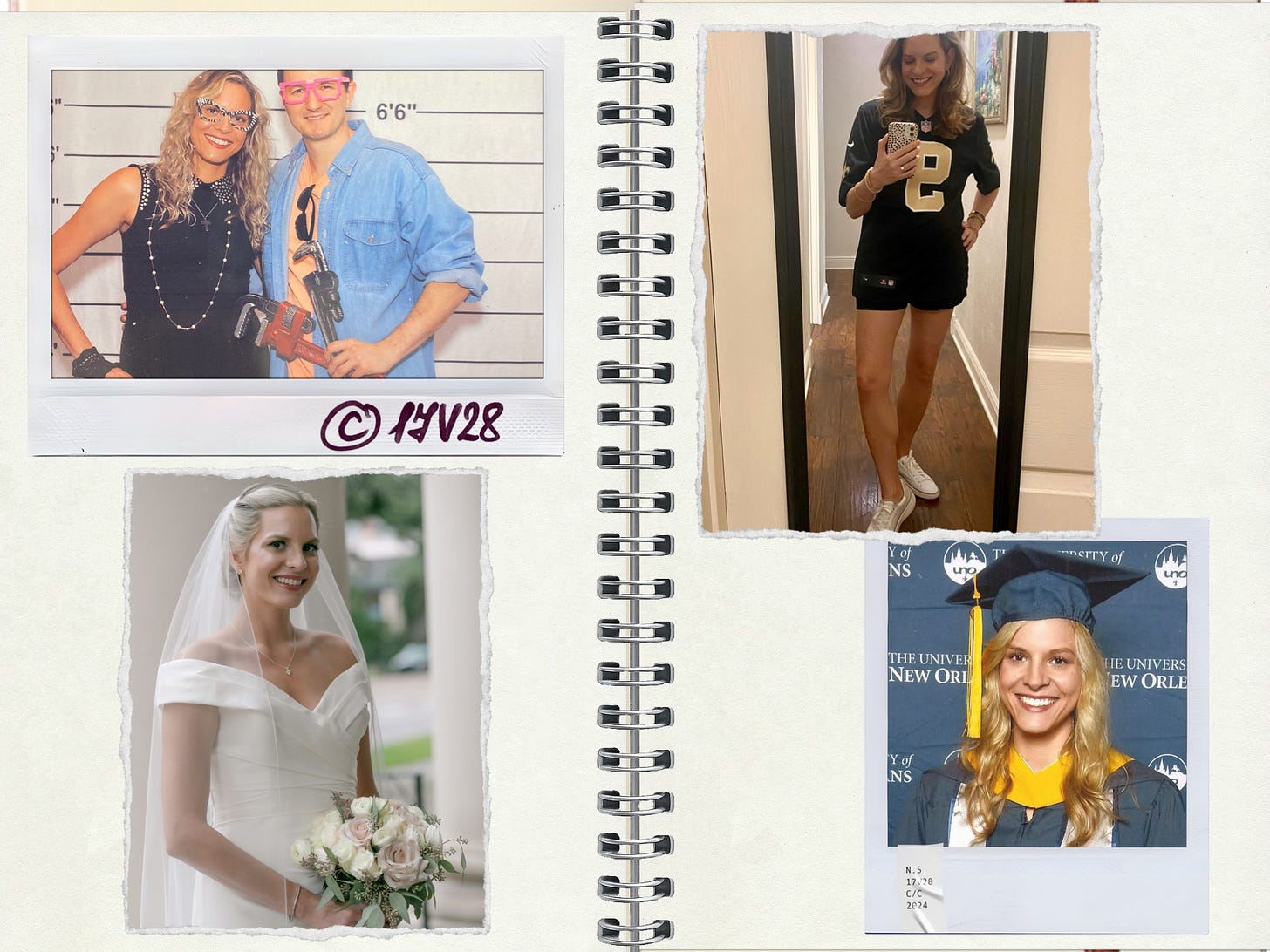

Sure, I’ve tried on plenty of “costumes” throughout my life. The college sorority theme party costume. The young professional “Corporate Courtney” costume. The festival-going, footloose and fancy free costume. The blushing bride-to-be trying on gowns, champagne flute-in-hand, costume. The Mardi Gras ball dressed to the nines costume.

There were so many vibrant tones and shades of exploration across the decades. But where are all those different versions of myself now? Some are folded up neatly and tucked away. Some cease to exist all together. Some are forgotten.

And honestly? I miss them. I miss the woman who tried things on just to see how they felt, before life became about meeting expectations rather than exploring possibilities. I am at a stage in my life where I am so focused on meeting expectations that I have very little bandwidth available for that type of exploration.

Ralphie’s voice snaps me back to the present moment.

“We’re ready!” Ralphie announces with newfound authority.

“Yes! Y’all are SO ready!” I reply reassuringly.

Then, I find myself wondering: ready for what, exactly? Regardless of that answer, the maskenfreiheit is alive and all the world is my sons’ stage right now. I love having a front-row seat to this little Halloween “dress rehearsal.”

Dressing the Part

Later that evening, after the boys are asleep, I change into my PJs and cocoon myself up in a cozy blanket with a cup of chamomile lavender tea and a book by my side. The simplicity of this moment, wrapped up in the stillness of the present moment, is so sublime. Maybe this is my best costume yet.

Tonight’s little “dress rehearsal” with my boys made me remember my own dress rehearsals—not one for Halloween, but one for identity itself. Let’s rewind back to another Tuesday night in October.

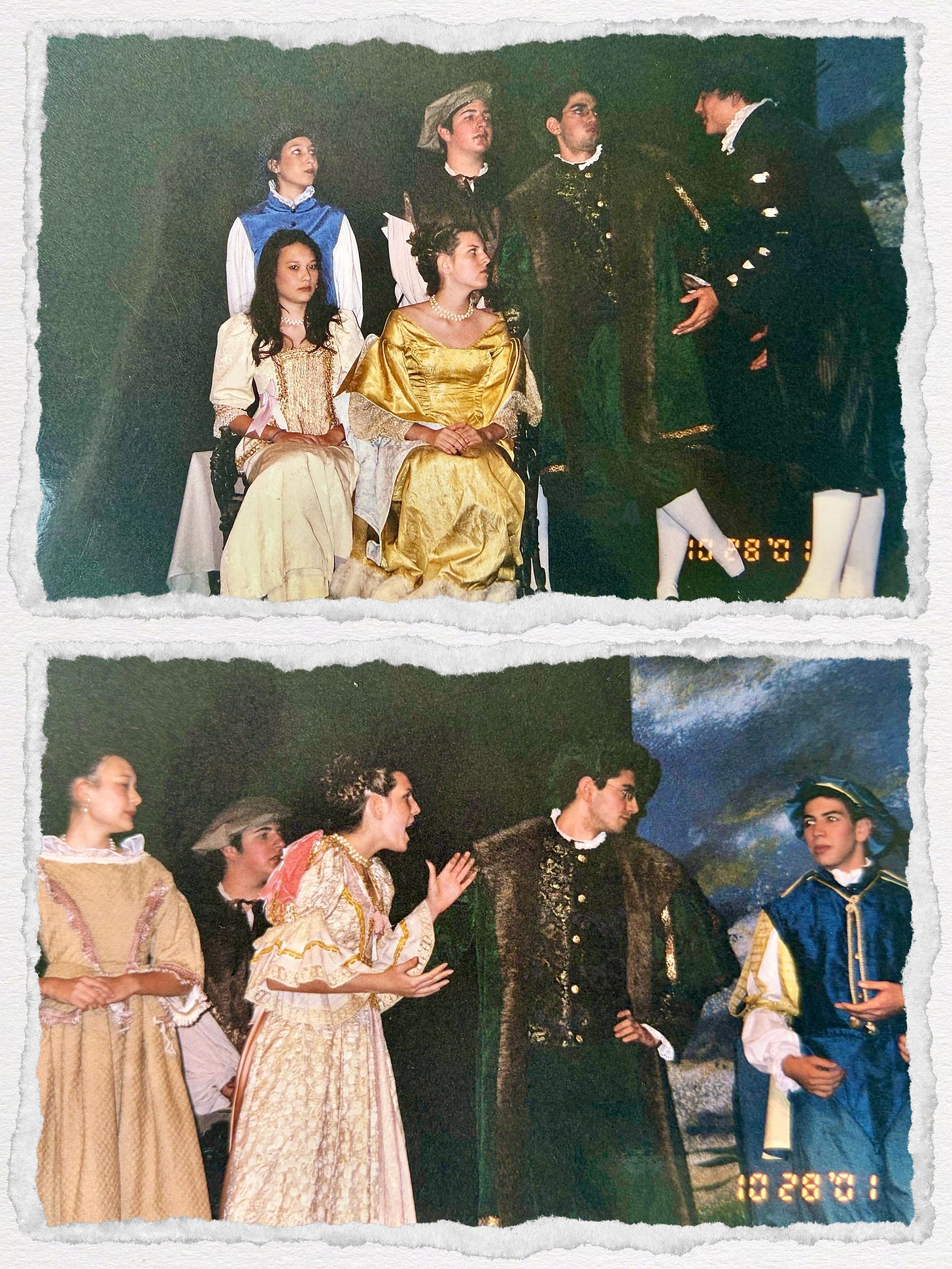

It’s 2001. It was my Junior year of high school, and for months, I had been rehearsing for our fall production of The Taming of the Shrew. Being cast as Katherina, the titular “shrew,” was my first adolescent foray in unlearning femininity. I bid adieu to that “very mindful, very demure” mindset, the very nuts and bolts of my entire personality and adolescent identity.

Farewell, soft spoken tone of voice. Farewell, saccharine smile. Farewell, polished politeness.

Instead, I could be overbearing. Harsh. Loud. Assertive. IDGAF through and through.

Katherina was like the freaking Courtney Love of the Shakespearean realm!

But you know what? She was fun! And I grew to relish having an “excuse” to explore these completely novel characteristics. Yes, Katherina was an utter hot mess of a character, but at least she was an authentic hot mess. She was unapologetically herself. That is, until Petruchio entered the scene.

Now here’s where the plot (and the night of that dress rehearsal) really gains momentum.

My director, Cassie, calls me on stage—along with my classmate, Josh, who was cast as Petruchio, the “tamer” who vowed to marry Katherina for his own monetary gains. I’m feeling confident as I take my place on stage. I’m wearing this gorgeous ultra form fitting golden gown, and I’m ready to rock and let some heads roll.

We get to the part in the scene where Petruchio has to deliver this line:

“ We will have rings and things and fine array; And kiss me, Kate , we will be married o’Sunday”

And that’s where Cassie stops him mid-line to inform us that we’re about to practice the stage kiss for the first time.

But here’s the thing: I have never been kissed. So imagine how painfully awkward it was for me in that moment to have my first ever kiss—on stage—in front of a bunch of my peers and faculty.

I tell myself to play it cool as I’m taking literal direction on how to be kissed. Petruchio spins me and dips me down, the gown’s train swooshing on the floor. I close my eyes for the kiss and pray that we don’t have to repeat this scene again tonight.

I’ll never forget that dress rehearsal because it epitomizes what it meant to truly step outside of my comfort zone while staying in character. Looking back, that stage gave me permission to try on an identity I never would have claimed as my own—loud, harsh, unapologetically herself. The costume made it safe to experiment.

Somewhere between then and now, I stopped giving myself permission to experiment. When did trying on new identities stop being play and start feeling like risk?

Which raises the question: what’s actually happening psychologically when we put on a costume? Why does it create this sense of freedom—this maskenfreiheit—in the first place?”

There’s actually science that helps explain both what I felt then and what my sons experienced this evening. The maskenfreiheit phenomenon all relates back to what researchers call “enclothed cognition“—the systematic influence that clothes have on the wearer’s psychological processes.

In a groundbreaking study by Northwestern University researchers Hajo Adam and Adam Galinsky, participants who wore lab coats described as “doctors’ coats” performed significantly better on attention-related tasks than those who wore identical lab coats that were described as “painters’ coats.”

Adam and Galinsky’s studies demonstrated that the influence of clothing on cognitive performance depends on two critical factors: the symbolic meaning of the clothes and the physical experience of wearing them. The participants who merely looked at a doctor’s coat or wrote about it didn’t experience the same cognitive benefits as those who actually wore the coat, suggesting that the physical embodiment of the clothing’s symbolic meaning is crucial for the psychological transformation to occur.

The research on enclothed cognition shows how our everyday “costumes” operate on the same psychological principles as Halloween outfits, but with less dramatic flair. They’re identity cues that help us transition between roles and access different aspects of our personality.

Finding what fits

I take a sip of my tea, mentally shuffling around hangars in my head. Rows and rows of exploration. Taking inventory, it becomes clear that there are costumes that fit, costumes that never quite fit, and costumes that connect.

My current mom uniform—yoga pants, athletic top, sneakers, travel mug of café au lait—isn’t really a costume at all anymore. It’s just me. This “less is more” approach to fashion embodies a wellness mindset that feels genuinely aligned with who I am at this stage of life. When I put on these clothes, I’m inhabiting motherhood comfortably. The costume has become the person, or maybe the person has finally found the costume that fits.

The blazer, though? That’s a different story. Wearing business suits for past corporate roles definitely helped me access confidence and authority in professional settings. It was part of putting my best face forward, embodying that “girl boss” mindset I grew up believing I should want. But did it feel authentic? Not really. It felt like playing a part I’d been told I should want to land. I was good at it, but it never stopped feeling like a costume—the kind you’re relieved to take off at the end of the day. And I notice that even on Zoom calls now, when I dress “professionally” from the waist up, I’m performing a version of myself that I’m not sure I miss.

Then there are the costumes that aren’t about individual identity at all, but about belonging to something larger than yourself. Down here in bayou country, wearing the black and gold—sporting a New Orleans Saints jersey on game day—is all about embracing our collective cultural identity. We “bleed black and gold” because it’s woven into the fabric of who we are as a community, even when the team is, well, dropping the ball in more ways than one this season. This costume announces where I belong—in the Who Dat nation.

And here’s what I’m realizing as I mentally sort through my own wardrobe of identities: some costumes feel like authentic extensions of who I am, some feel like necessary performances, and some—I’m starting to suspect—are masks I’m ready to take off.

I finish my last sip of tea and close the pages shut, ready to turn in for the night. I unwrap myself from my blanket, my cocoon of comfort. Maybe we’re all just cocooned in different costumes and identities before we emerge in our final forms. Before our metamorphosis is complete.

This Tuesday evening in October was one of many stages of exploration in that beautiful process of identity metamorphosis—just like all those years ago on that high school stage. But what strikes me is how the stages shift over the course of a lifetime: as children and young adults, the exploration feels lighter, freer, unburdened by the weight of ‘figuring out’ who they’re supposed to become.

Children are trying on identities to see what fits. Adults have a tendency to perform identities that have already been assigned, be it from society or assigned to one’s self and maybe never reconsidered. Childrens’ costumes are questions: What if I was brave? What if I could fly? As we age, ours become answers: This is who I am. This is what I do. This is where I belong.

At forty, I’m at a stage in life where I’m supposed to have my identity “figured out.” But what if I’m wrong? What if at forty, I’m not supposed to have it all figured out? What if there are still identities worth trying on, qualities worth experimenting with, versions of myself I haven’t met yet?

I may not be at the literal or figurative stage in life where I’m a shrew being tamed for entertainment’s sake, but that doesn’t mean the maskenfreiheit has exited stage left as well. It still exists, just in a different context.

In this current season of life, I get the pleasure of experiencing that maskenfreiheit vicariously through my sons. I get to see the world through their masks. Their wonder. Their imaginations. And it turns out, this is just as psychologically liberating, if not more so, because it’s wrapped in so many layers of experience and perspective.

Maybe it’s not putting on, but rather, taking off the mask that’s the most liberating act of them all. Because deep down, you know that clothes do not make the man, but they do make the mindset, and sometimes—that makes all the difference.

Pause and Reflect:

What did you dress up as as a child, and what aspect of yourself were you exploring through that costume? Did you integrate that quality into your adult identity, or did you leave it behind?

If you could experience maskenfreiheit—the freedom that comes from wearing a mask—what identity would you try on?

The Science Behind the Insights

The research on enclothed cognition provides compelling evidence for why costumes have such powerful psychological effects. When we put on certain clothing, we’re changing our cognitive and behavioral patterns through the process of embodiment.

But the deeper question—why costume exploration matters for development—connects to psychologist James Marcia’s influential work on identity formation. Marcia identified exploration and commitment as two key dimensions of identity development, noting that individuals must actively investigate various options and possibilities before making authentic commitments to particular identity paths.

In his framework, the healthiest identity development occurs when people engage in active exploration before committing to who they want to be, rather than simply accepting assigned identities or avoiding the exploration process altogether.

Halloween costumes, theatrical roles, and even the everyday “costumes” we wear provide low-stakes ways to engage in this crucial exploration process. We can try on different ways of being, observe how others respond, and notice what feels authentic or empowering. This experimentation helps us develop a clearer sense of our own preferences, values, and capabilities—not just in childhood, but across the lifespan.

What Marcia’s work suggests, and what I’m realizing watching my sons discover maskenfreiheit, is that identity exploration isn’t something we finish in adolescence. The costumes change, the stakes shift, but the need to try on new possibilities remains.

References:

Adam, H., & Galinsky, A. D. (2012). Enclothed cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4), 918-925.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159-187). Wiley.

"I am so focused on meeting expectations that I have very little bandwidth available for that type of exploration."

Ha! Love the idea of "bandwidth availability"-- that's definitely a problem for a lot of us these days!

I've done some community theater, and yes, it's a real kick to "put on a mask" and be someone else for a while. 🎭👍

Love this piece and your wicked tales 💕 Also, learning new words again from Ms. Ambrosia: maskenfreiheit and "enclothed cognition!" It's great to learn terms for these things I've noticed but not sure how to describe it. I loved how you interwove the dress rehearsal, masks, stage symbolically throughout your whole narrative! (P.S. I think we've gone through very similar life stages around the same time!)

To answer your question: as a mid-age child, I frequently dressed as a court jester for Halloween-- my mom made me a custom costume so I wore it multiple times. At the time, I was really into the Harley Quinn character in the Batman TV series (this is back in the 90's before her mainstream adaption). Thinking about what must have appealed was her rebellious nature and break from conformity, she seemed liberated and at ease. I don't integrate that quality into my adult identity full-on but I still admire those attributes.